Social media posts claim the Atlantic Ocean’s plankton population has suffered a decimating fall of 90 percent, citing research from marine biologists. But the claim is false; the article — which the author described as an “observation think piece” that was never “intended to be peer-reviewed” — only covers one part of the ocean, and independent scientists say there is no evidence plankton activity has decreased by such a large margin.

“Scientists reveal our empty oceans. Research: 90% of Atlantic plankton lost,” says the headline of a front-page story from The Sunday Post, a Scottish newspaper, published July 17, 2022.

The same claim then gathered thousands of likes and shares on social media after Netflix documentary “Seaspiracy” and charity project Save the Reef shared it.

Screenshot of the July 17, 2022 front page of The Sunday Post

Screenshot of the July 17, 2022 front page of The Sunday Post Screenshot of an Instagram post taken July 26, 2022

Screenshot of an Instagram post taken July 26, 2022According to the National Oceanic and Athmospheric Administration (NOAA), plankton can be categorized into two main groups: “phytoplankton (plants) and zooplankton (animals).” They play a crucial role in ocean ecosystems.

Climate change has had an effect on the habitat of plankton. But the claims shared online are false.

Scientists say 90% of plankton have not disappeared from the Atlantic Ocean — and that if they had, it would have created significant and visible disruptions in marine life.

Researcher amends claims

The Sunday Post article is based on a project from Howard Dryden and Caroline Duncan, marine biologists at the Global Oceanic Environmental Survey (GOES) Foundation.

Their piece, titled “Climate Change…Equatorial Atlantic Ocean plankton productivity and Caribbean pollution….a think piece for debate,” draws upon “plankton sampling activity and other observations” to conclude that plankton losses “closer to 90% have occurred.”

But Dryden said the project never covered the whole Atlantic Ocean, as the posts and The Sunday Post article claim.

“There have been mistakes made in reporting our results, we may have been inadvertently responsible by not communicating properly, but I wish to make the statement that the results only apply to the Equatorial region of the Atlantic Ocean,” he said in a statement sent to AFP.

Dryden added that the report, which underwent revisions, is an “observation think piece” — not a peer-reviewed scientific study.

“This is just an initial observation and comment on the results obtained, there was no intention to have the document peer-reviewed,” he said.

The marine biologist told AFP the statement about a 90% reduction in plankton productivity in the region was a “prediction” based on other data and reports.

The headline of the online version of The Sunday Post’s story has been updated, and a note was added to the bottom of the piece.

“This story was edited on 23 July 2022 to make clear the samples studied by the Global Oceanic Environmental Survey Foundation were taken from the equatorial Atlantic and have not yet been confirmed by other scientists or research teams,” the note says.

Jim Wilson, editor of The Sunday Post, told AFP in an email that the newspaper “denies misrepresenting the research and stands by its reporting.”

“We accurately reported Dr. Dryden’s research,” he said. “Our headline might have been more specific about the geographical limits of that research but the story was clear and would have left no fair-minded reader confused.”

Scientists question findings

But several independent scientists urged caution after reviewing Dryden and Duncan’s piece, pointing to an absence of a transparent methodology used to collect and analyze data.

“We cannot trust the findings presented in this report,” Marie-Fanny Racault, a biological oceanographer who studies climate impact on marine ecosystem resources, told AFP.

Racault, lead author of a chapter on ocean and coastal ecosystems for the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports, said the claim that 90% of plankton are gone from the Atlantic Ocean is “not supported by robust scientific evidence.”

“No baseline reference is given, ‘90% gone’ but since when? Or compared to what period or conditions?” she said. “Further, the report fails to account for previous findings reported in published peer-reviewed scientific literature.”

Marine conservation ecologist Abigail McQuatters-Gollop, who leads plankton expert groups for the Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic (OSPAR), echoed Racault’s concerns.

“It is very difficult to identify real changes in oceanic variables (as opposed to natural variability) without at least 20 years of data,” she told AFP, adding that “plankton identification is a tricky skill.”

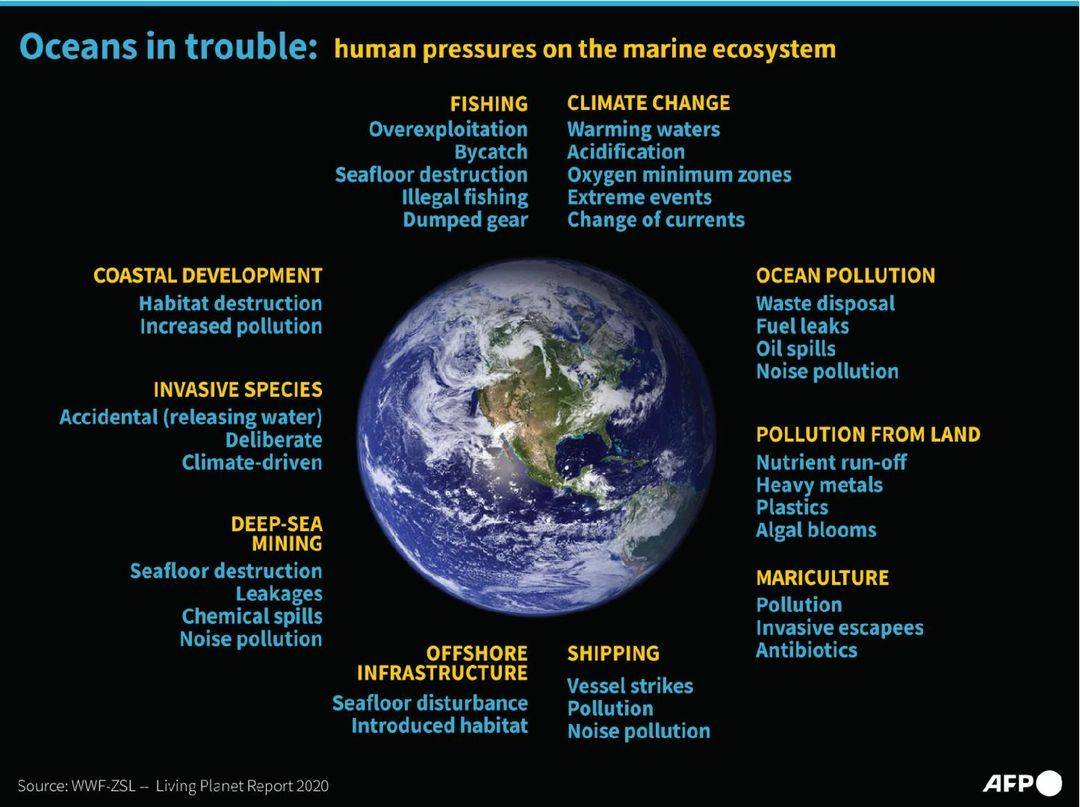

Environmental damage in oceans caused by human activity

Environmental damage in oceans caused by human activityMcQuatters-Gollop’s teams work with hundreds of thousands of plankton samples, collected over 80 years from 14 different countries.

“This is compared to the 500 samples used in the paper whose collection and analysis methodology is not described,” she said.

The scientist told AFP that “if any aspect of plankton had changed by 90% recently,” the consequences would be felt in many areas, such as fisheries.

“A catastrophic change in productivity like that described by Dryden would be much more obvious than what has currently been observed, with likely a collapse or near-collapse of the Atlantic marine food web,” McQuatters-Gollop said.

However, the fact that the claims shared online are inaccurate does not mean climate change is not a threat to plankton.

The most recent IPCC assessment report indicates ocean warming and changes in sea ice are among the main drivers affecting plankton productivity.

“There is no doubt that ongoing and future climate change and ocean acidification are altering the ocean environment,” said Alessandro Tagliabue, an ocean biogeochemist at the University of Liverpool. “Understanding how these changes will affect plankton productivity is one of the grand challenges facing the oceanographic and marine science communities.”

AFP has fact-checked other claims about the environment here.