A Facebook post shared thousands of times claims that chewing the bark of the cashew tree will “destroy snake venom”, including the highly toxic bite from a black mamba. This is false: experts say only antivenoms can counteract the effects of a venomous snake bite and that herbal or other traditional remedies serve no purpose in neutralising the toxins.

“If you are a victim of snakes bites or poison, just look for a cashew tree, use your cutlass to get the bark of the cashew tree, and chew the bark of the tree (sic),” reads a post published on September 26, 2022.

A screenshot of the false Facebook post, taken on October 2, 2022

A screenshot of the false Facebook post, taken on October 2, 2022

Swallowing the juice secreted from chewing the bark “will neutralize every poisonous substance,” including the venom of a black mamba snake, it adds.

Indigenous to southern and eastern Africa, the black mamba is considered one of the world’s deadliest snakes, with its bite capable of killing within hours.

The post has been shared more than 13,000 times and was published by a Facebook account promoting traditional medicines.

The same post is also circulating on WhatsApp and was posted elsewhere on Facebook here, here and here.

A screenshot of the false claim circulating on WhatsApp, taken on October 3, 2022

A screenshot of the false claim circulating on WhatsApp, taken on October 3, 2022

Nigeria’s ministry of health said snakes kill about 2,000 people annually and that the country has “limited availability of anti-snake venom”, a vial of which can cost up to 55,000 naira (about $128), almost double the country’s minimum wage of 30,000 naira (about $70).

The cost and limited supply of antivenom have created a gap being exploited by traditional medicine practitioners.

But the claim that chewing the bark of cashew trees cures snake bites is false.

‘Herbs do not work’

The World Health Organization (WHO) advises that in the event of a snake bite, traditional and herbal treatments should be avoided. “Antivenoms remain the only specific treatment that can potentially prevent or reverse most of the effects of snakebite envenoming when administered early in an adequate therapeutic dose.”

Johan Marais, a snake bite expert at the African Snakebite Institute (ASI) in South Africa, told AFP Fact Check that the claim in the Facebook post is not “true at all”.

He explained that while it is possible, for instance, to “neutralise” snake venom with petrol, it does not imply it should be injected into the body as a cure.

“So, to eat or chew cashew nuts or the bark of the tree does nothing to neutralise the venom of a snake,” Marais said.

Indigenous to southern and eastern Africa, the black mamba is considered one of the world’s deadliest snakes

Indigenous to southern and eastern Africa, the black mamba is considered one of the world’s deadliest snakes

Sulaiman Mohammed, the principal medical officer at the Snakebites Research and Treatment Centre in Kaltungo, Gombe state, told a Nigerian news agency earlier this year that herbs do not work. He said people should “embrace orthodox treatment” and get to a hospital as soon as possible to give themselves the best shot at recovery.

Snake venom

The toxin in snake bites varies based on the species or subspecies of snakes and falls into three categories, according to a blog post by the ASI.

Snakes such as the black mamba mentioned in the claim have neurotoxic venom that affects the nervous system. Cytotoxic venom attacks the tissue and muscle cells at the site of the bite while haemotoxic venom impacts the blood’s clotting mechanism. The World Health Organization (WHO) adds myotoxic venom to its list. Dangers include paralysis of breathing.

Some snakes, however, produce venom containing more than one toxin.

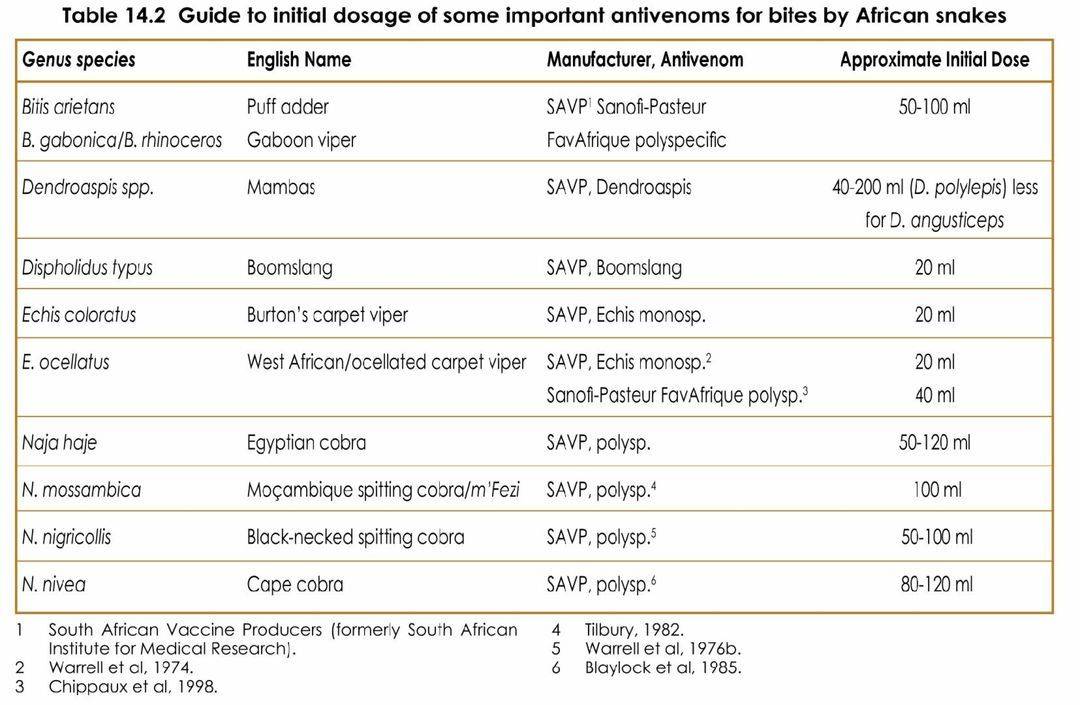

WHO’s guidelines for treating snake bites identify two broad categories of anti-snake venoms — monospecific and polyspecific antivenoms.

Monospecific antivenoms should be used if the species of snake that causes the bite is known while polyspecific could be administered if the snake is unidentified.

A screenshot shows WHO guide to initial dosage of some antivenoms for bites by African snakes, taken October 2, 2022

A screenshot shows WHO guide to initial dosage of some antivenoms for bites by African snakes, taken October 2, 2022

What is antivenom?

University of Melbourne’s School of Biomedical Sciences explains that antivenoms are “purified antibodies” derived from animals – in most cases horses – that have been injected with non-harmful doses of snake venom.

Over time, about nine months, the animal’s tolerance and antibodies build up as larger doses of venom are administered.

“These antibodies are harvested by taking blood from the animals and separating out the antibodies, which are then fragmented and purified by a series of digestion and processing steps,” the university’s website says.

When a patient receives an antidote, the “binding sites on the antibody fragments bind to the venoms or venom components” in the blood and effectively neutralise them.

According to ASI, the production of antivenom takes “many years” because each serum is subjected to clinical trials. This makes its development expensive and accounts for the “reason we only have antivenom for those snakes that have caused fatalities in the past”.

In South Africa, the antivenom exists for 10 snake species, including the black mamba.