Social media posts and online articles claim polar bears are growing in number, citing it as evidence that the threat of climate change is exaggerated. This is misleading; scientists say there is not enough data to show a rising trend in polar bear numbers, and the impact of climate change on their habitat is widely documented.

“The Climate Change people are a Cult. They think made up truth is the truth,” says a January 11, 2022 Facebook post linking to an article that claims polar bears went up in number from between 5,000 and 10,000 in the 1950s to as high as 39,000 today.

Screenshot of a Facebook post taken on January 28, 2022

Screenshot of a Facebook post taken on January 28, 2022Such claims have circulated on social media for years — part of a broader trend of inaccurate information spreading online about climate change and its effects.

Researchers have credited the estimate of 5,000 polar bears in the 1950s to the respected Russian biologist Savva Uspenski. He gave a range of 5,000 to 10,000 bears in papers citing his studies in the Soviet Arctic in the 1960s.

Other scientists have since rejected the estimate.

The numbers from the 1950s and 1960s “are just not reliable,” Steven Amstrup, chief scientist at the conservation group Polar Bears International, told AFP. “There is no evidence that global numbers of polar bears have increased.”

Amstrup is one of nine experts cited in the 2021 polar bear assessment by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). It says on its red list of threatened species that the population trend for polar bears is “unknown.”

Some populations increased thanks to hunting restrictions from 1973, but researchers at the University of Alberta told Climate Feedback that meaningful global data was lacking before the late 1970s.

Numerous studies have shown the impact on polar bears of climate change and shrinking sea ice and the threat these pose to their habitat. The melting of sea ice on which polar bears rely to catch the seals they eat is documented in sources including the latest United Nations climate change report.

Changes in Arctic sea-ice from 1980 to 2020 ( AFP / Simon Malfatto)

Changes in Arctic sea-ice from 1980 to 2020 ( AFP / Simon Malfatto)Climate change skeptics

The article linked to in the January 11 Facebook post is by Climate Realism, a climate change skeptic site run by the US think-tank the Heartland Institute. Its history of receiving funding from the energy industry is documented by the investigative climate site DeSmog.

The Climate Realism article links to another on a page run by the Heartland Institute.

It and numerous others cite as their sources a report and a book by zoologist Susan Crockford. Her report says that since the IUCN’s most recent assessment, additional surveys have shown polar bear populations in three regions to be stable or increasing. The book defends Uspenski’s 5,000 estimate, arguing that it was based on the best methods available at the time.

Crockford’s report lists hundreds of scientific papers among its sources but was not itself published in a science journal.

Instead, it was released by the Global Warming Policy Foundation (GWPF), a UK-based group that describes itself as a think tank and educational charity aiming to scrutinise climate change mitigation policies that “may be doing more harm than good.” It says its reports are peer-reviewed by its Academic Advisory Council.

The GWPF has said it does not challenge the basic science on human-caused climate change, but one report it published cast doubt on the consensus that carbon dioxide emissions are driving warming. Various declarations from its members are documented by DeSmog.

Factfile on polar bears, whose survival is threatened by global warming and related threats ( AFP / Adrian Leung, John Saeki)

Factfile on polar bears, whose survival is threatened by global warming and related threats ( AFP / Adrian Leung, John Saeki)Data deficiency

Polar bears are hard to track, roaming on the ice in remote regions of the Arctic where they blend into the white landscape. In some places, researchers put tags on the bears to monitor them. In other regions, the bears are little observed because it is too expensive or too dangerous. Scientists plug the gap in estimates by other methods.

The IUCN is an international conservation union that counts 1,400 governments and civil groups among its members. The most recent estimate by its Polar Bear Specialist Group (PBSG) for the global polar bear population is 26,000 — an average from a range of 22,000 to 31,000.

This “is a combination of solid estimates from several populations and educated guesses from those for which we have little data,” Amstrup said.

The count “has been increased in recent years because we have learned that some of our old estimates in the poorly documented areas may have been too low,” said Amstrup. “This doesn’t mean those populations have grown, but rather that the initial estimates were simply too small.”

Key facts about the polar bear, apex predator of the Arctic ( AFP / Jonathan Walter, Laurence Saubadu, John Saeki)

Key facts about the polar bear, apex predator of the Arctic ( AFP / Jonathan Walter, Laurence Saubadu, John Saeki)On page 52 of its latest report, the PBSG says that over a past generation of polar bears, or 11.5-years, 10 of the subpopulations surveyed were marked “data deficient.” Of the nine others, two were estimated to have “likely increased” and four were “likely stable.” Three were estimated to have “likely decreased.”

Looking back over two or more generations, there was insufficient data for 16 of the 19 subpopulations that make up the global headcount. The most recent data cited is from 2017, for the Gulf of Boothia in Canada.

Further back, “there is no data to support any calculations on the number of polar bears in 1950… This is pure speculation,” Dag Vongraven, a senior adviser to the Norwegian Polar Institute, said in August 2021.

“There was hardly anything done on polar bear research prior to the late 1960s,” he said for an AFP article about similar claims made in a German video. “Even today we have little or no knowledge of polar bears and numbers in half of their area of occupancy.”

Vongraven was a joint author of a study published in 2018 that surveyed the quantity of research on polar bears published from the 1960s to the 2010s.

Habitat threatened

The bears are listed as threatened under the US Endangered Species Act and as a species of “special concern” by the Canadian government. The IUCN has listed polar bears as vulnerable since 1982. All three current listings cite climate change as the reason.

Despite the lack of data for past decades, scientists can now project future trends if climate change trends continue.

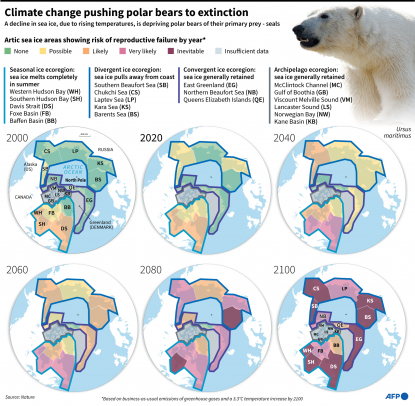

Maps of polar bear populations, showing the projected progression towards extinction in many areas ( AFP / Jonathan Walter, Laurence Saubadu)

Maps of polar bear populations, showing the projected progression towards extinction in many areas ( AFP / Jonathan Walter, Laurence Saubadu)“The most well-studied sub-populations show that as sea ice has become less and less available, polar bear body condition has declined, recruitment (reproduction) has been reduced, and population sizes have declined,” said Amstrup.

A 2020 study concluded that on current trends, polar bears in 12 of 13 subpopulations analysed will have been decimated within 80 years by climate change. The study was published in the journal Nature Climate Change, an international reference for scientific research.

“No matter how many bears there are out there, if there are too many ice free days, female bears will not have sufficient fat reserves to nurse their cubs, and cubs will start dying at a rapid rate,” Amstrup said. “Frequent years with too many ice free days assure population decline.”